Can four migratory bird species keep track of the UK's early springs?

Hazel Shipsey BSc, University of Liverpool, 26/06/2025

The UK has experienced record breaking spring temperatures for the second year running (Met Office). This coincides with recent research evidencing an earlier onset of spring across the norther hemisphere, which raises a critical question: will the UK's native wildlife be able to keep pace with these seasonal shifts?

For her final-year Environmental Science research project, Hazel explored whether four long-distance migratory birds, which visit the UK to breed, are keeping track with changes in spring phenology.

To track the timing of spring phenological events in the UK, a total of 356 900 observations from the Nature's Calendar database were analysed over a 21-year study period.

Is spring getting earlier in the UK?

Using 10 indicators of the onset of spring, she found evidence that spring is advancing, consistent with previous research using Nature’s Calendar data. Specifically, 60 % of indicators showed an advancement of more than 1 day per decade. Overall, spring advanced by nearly a full day for every 1ºC rise in average spring temperatures, meaning warmer springs in the UK will bring an earlier start to the season.

Can birds migrating to the UK track change in the timing of spring?

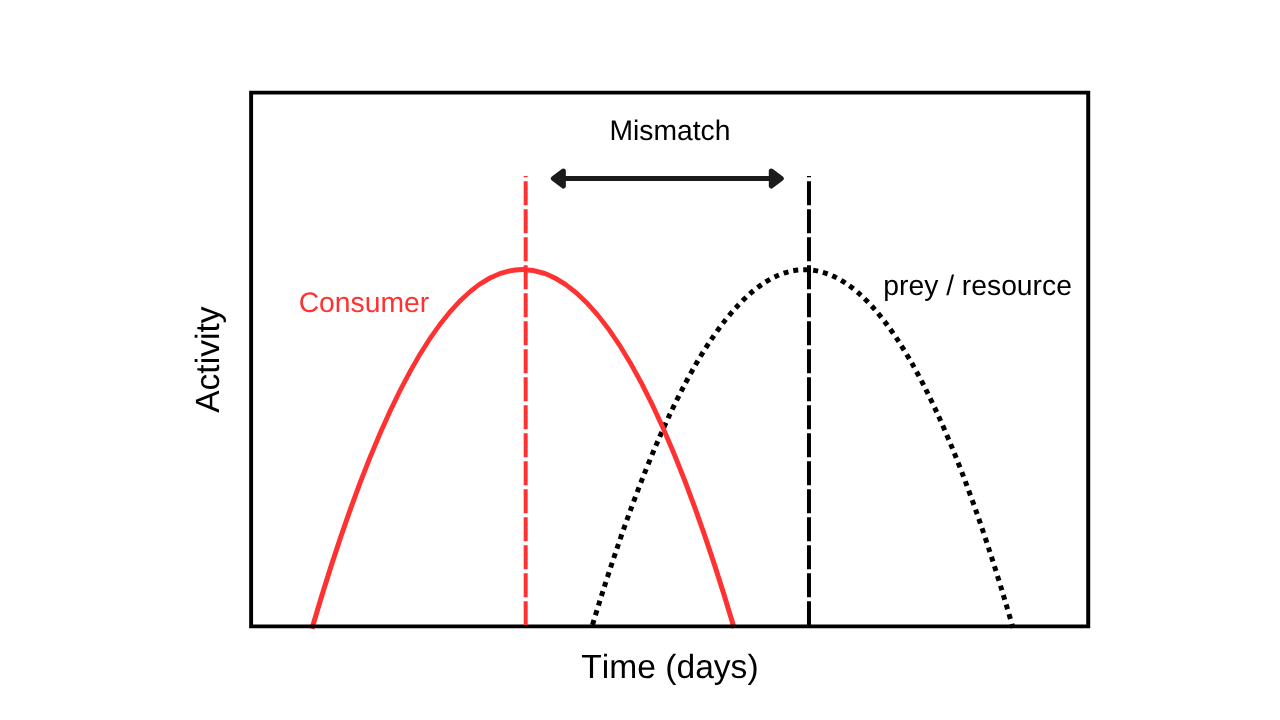

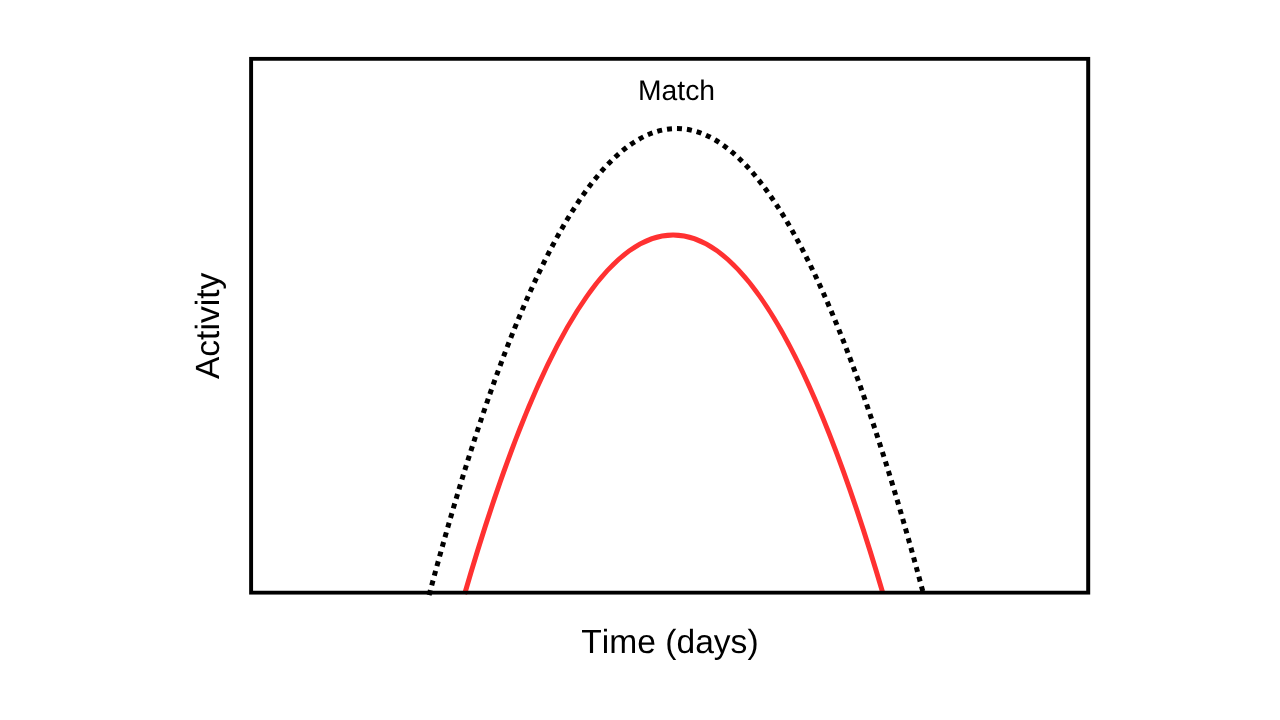

Climate change is increasing the risk of phenological mismatch since different species respond to environmental changes at different rates. This is particularly relevant for migratory birds, which travel thousands of miles between their wintering and breeding grounds. These species migrate with limited ability to detect the conditions waiting for them in the UK, and as a result are at an increased risk of mistiming arrival with the short window of optimal habitat conditions and food availability.

Figure 1: A visual representation of phenological mismatch. The dashed black line shows the timing of peak resource availability (e.g. insects), and the red line shows the timing of peak consumer activity (e.g. migratory birds). When these peaks are misaligned, phenological mismatch will occur as peak consumer activity doesn’t synchronise with peak resource availability.

To find out whether migratory birds are keeping pace with the UK’s shifting spring, Hazel looked at the arrival records of four species over the same time period: house martin (Delichon urbicum), swallow (Hirundo rustica), swift (Apus apus) and willow warbler (Phylloscopus trochilus). The results showed clear differences in how these birds are tracking changes in the timing of spring.

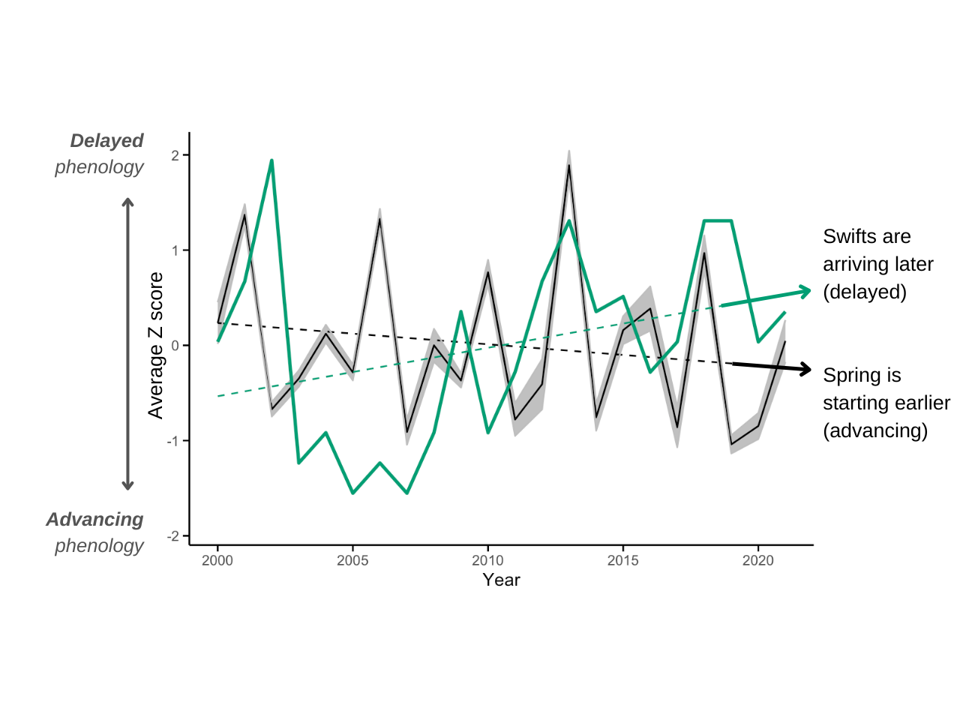

Swallows are arriving more than 2 days earlier per decade, showing the species is responding to environmental change. However, the shift is happening twice as fast as many spring events, meaning they may risk arriving before optimal conditions. In contrast, swifts are arriving almost two days later per decade – the opposite trend to changes in the timing of our spring – creating a long term delay that puts the species at risk of increased mismatch with key spring events. Both house martins and willow warblers appear to be better at adapting migration timing, showing well matched arrival timing with the onset of spring events.

Figure 2: Time-series data of swift arrival dates in green and the spring index in black, depicting an earlier arrival of spring and conversely a delayed arrival of swifts to the UK. Z-scores were used in the standardisation process for the spring index (full methodology can be found in the main body of the dissertation).

Whilst the study didn’t directly measure the impacts of mismatch between arrival timing and the onset of spring for these bird species, previous research has emphasised the consequences for migratory birds. For insectivorous migratory birds, their survival and reproductive success is dependent on arriving at their breeding grounds in time for a short window of optimal habitat conditions and peak insect abundance. Species like swifts which are showing evidence of arriving increasingly later than the start of spring face an increased risk of population decline driven by this mismatch. This isn’t just a local issue, climate change has already driven population decline and even regional extinctions in migratory birds worldwide. However, with continued research and targeted conservation efforts we will be able to better understand and protect our summer visitors.

“I’d like to express a huge thank you to everyone who participated in phenology recording for Nature’s Calendar for making this research possible. If you’d like to find out more, read my dissertation.” Hazel Shipsey

References

Met Office. https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/about-us/news-and-media/media-centre/weather-and-climate-news/2025/double-record-breaker-spring-2025-is-warmest-and-sunniest-on-uk-record#:~:text=Record%2Dbreaking%20temperatures,the%20series%20began%20in%201884.